In 1957, during preparation for their Christmas Day lunch, a couple living just outside of Basingstoke, Hampshire, were about to greet a very unexpected guest. Flying up their drive at 50mph was a small bearded man wearing three coats, and tree root sacking on his feet, sitting behind the wheel of a freewheeling experimental Formula Two race car, very much in need of a phone. The couple in question, apparently in a panic over the lateness of their expected guests, didn’t even notice this miniature Santa Claus, nor his peculiar set of wheels, as he waited patiently and dejectedly for his tow outside. It must have been quite a sight.

Motor racing journalist and correspondent Denis ‘Jenks’ Jenkinson was well known for his highly ambitious, and often illegal, road tests in the local area. However, this failed attempt to drive the Lotus Type 12 to its limits on 180 or so miles of public highways on Christmas Day was probably the most unusual and illicit of his life. And with Christmas 2020 looking to be one of the weirdest yet, we thought it was the perfect time to revisit his run – albeit in a more legal and safe manner.

The exact details of Jenkinson’s figure-of-eight course were lost with him in November 1996, but we have several clues to work from and, as there’s a healthy sprinkling of Lotus history in the area too, we’ve devised our own loop of the county in tribute. The car we’ve chosen, an Exige Cup 430, feels particularly appropriate too, looking every bit the race car for the road we needed to celebrate this great adventure. Joining me today as we exit the M3 at Camberley is editor Adam.

It’s a fitting place to begin our adventure. In March of the previous year, Jenkinson used the Surrey border town as the 3am starting point for his 130mph night run in a borrowed Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing. Jenkinson had no trouble handling high performance machinery, although he was known to go beyond their limits from time to time. He apparently spun the Mercedes off the road on a tight right-hander between Stockbridge and Romsey at great speed that day. Despite the setback, he managed to dust himself off, push the damaged supercar back onto the road and finish the test in a little over three hours. ‘Jenks’ was an accomplished racer in his own right on both two and four wheels, but it was his work as a co-driver on three and four that brought him the most success. In 1949, he became co-World Sidecar Champion with Eric Oliver on a Norton, and six years later he would pioneer pacenotes and guide Stirling Moss to victory at the Mille Miglia in the Mercedes-Benz 300SLR. It was perhaps this organised side that made his unusual road tests viable, and from what I can tell he was always a couple of steps ahead of the authorities.

Unlike the 300SL, the Lotus F2 racer wasn’t even close to being, or – crucially – looking, road legal. And with no lighting it wasn’t possible for him to attempt the usual secretive night run. Not one to be deterred, he decided he was to test the full fat race car on Christmas Day, specifically around the time when most families would be sitting down to their Christmas turkey. That way he could beat the traffic and hopefully make use of a little yuletide cheer should he come into contact with the Old Bill.

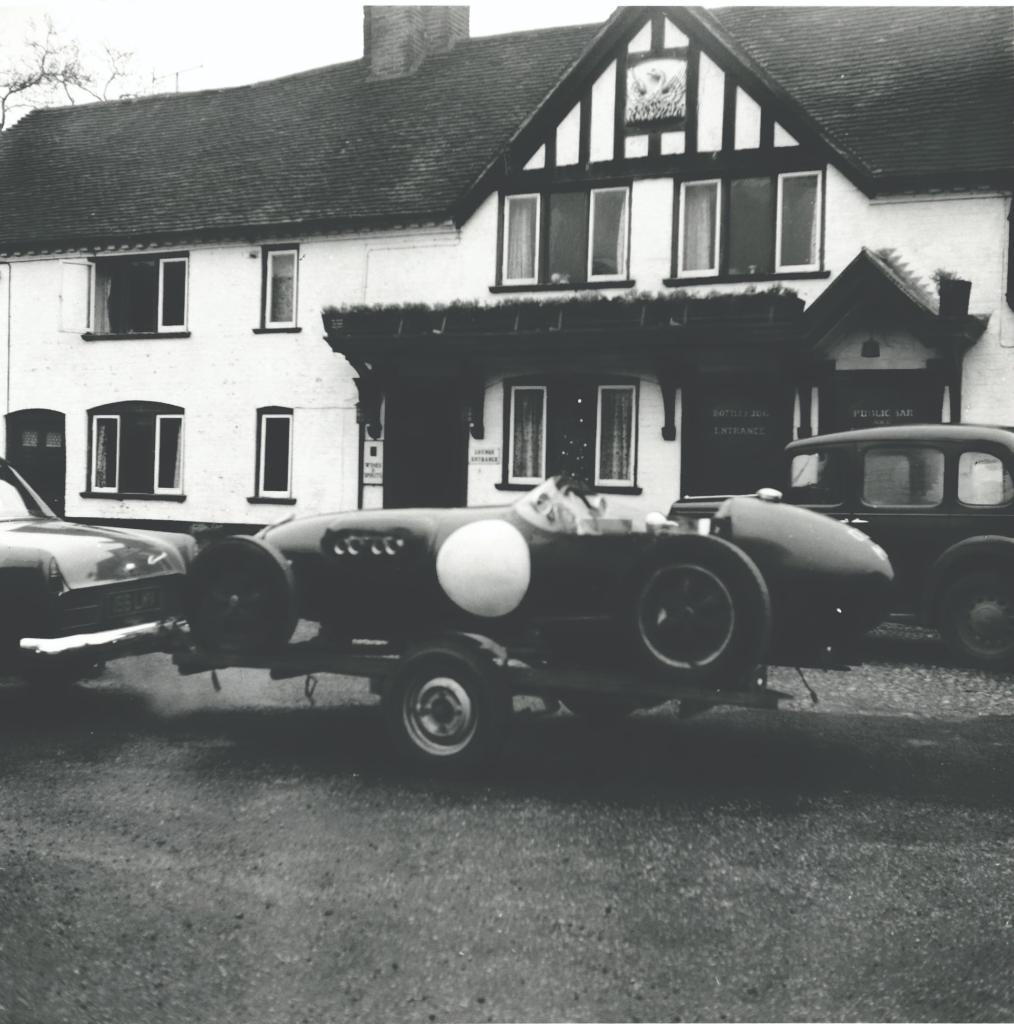

The plan was to meet Colin Chapman at the Phoenix Inn in Hartley Wintney at midday, which is exactly where, and when, our run starts today. It’s clear how much of a local legend Jenkinson was almost immediately as we’re greeted by the current landlady, who points us to the annex where he used to live. Today, it’s workshop that is appropriately used to restore vintage racing cars, and as we climb under the smallest doorframe I’ve ever seen, I can’t help but think it must have been the work of – as Motor Sport editor Bill Boddy sometimes referred to him – the bearded gnome. It’s clear Jenkinson left his mark on the town, and many here remember him fondly. He clearly liked the place, as his ashes were spread just across the road.

Seeing the Cup 430 sitting exactly where the Type 12 sat over 60 years ago, I can’t help but feel a little sentimental about the ill-fated original run. Lotus was chosen after the preferred Vanwall GP car fell through, due to co-founder Tony Vandervell getting cold feet about the potential for negative press regarding street testing – 140mph runs on the public highway would likely have been headline news if Jenkinson was caught. Chapman, who had a rebellious streak himself, was much more malleable to the idea. As he dropped the trailered F2 car off at this very carpark, he passed Jenkinson a set of trade plates and a crudely filled in testing slip, both of which he hoped would slow down the police if caught. Once the handover was made, Chapman swiftly departed for Hornsey, presumably to get back in time for his own Christmas dinner.

In a similar rush, we set off from the same side street as the Type 12, before taking the A303 for our first leg towards Andover. We soon pass through the same roundabouts to the edge of Basingstoke as Jenkinson, which he passed through at speeds of around 80 to 90mph, just warming the race car up for its gruelling all-county tour. The Exige, however, is all too happy to bounce along with the more plentiful 40mph traffic we’re sharing the road with today.

While feeling anti-socially loud as we head past the derestriction signs at the edges of towns, the fact we have a roof and heater does feel a little like cheating. Jenkinson had only his trademark beard, and several coats, to keep him warm on the big day as the gusts from the open Salisbury plains pushed over the lightweight, fully open Type 12, which was averaging 120mph on this stretch. Even for a seasoned racing driver, the F2 car had to have been a handful in the icy conditions. What’s more, his proposed course was over 13 times longer than the Nordschleife at the time. There was also the potential for slow moving traffic, horse effluent and the police around each and every blind bend, which made the course a real test of concentration, nerve, talent and, above all, luck. None of this, however, could stop Jenkinson from grabbing the Lotus by the scruff of its neck on his preferred highways and byways of Hampshire.

It was on this same stretch of road where he pushed the Type 12 beyond 120mph for the first time. He pushed the ‘Queerbox’ into top gear and the Lotus began to hurtle towards its terminal velocity, but suddenly the revs dropped. Being mechanically minded, Jenkinson knew something was very wrong with the transmission or drivetrain – later inspection found that a driveshaft had sheared. Disaster! Not wishing to break down by the side of the road, he freewheeled along the A303, when at 50mph he swerved up the drive of the unsuspecting couple preparing their Christmas meal, and contacted friend and editor Bill Boddy for a tow.

Thankfully, we have no such trouble with the Exige as we head beyond Andover. We may be nowhere near the Cup 430’s terminal velocity of 174mph, but its acceleration and sound above 4500rpm are nothing short of breathtaking on the road. The steering may feel particularly heavy at parking speeds, but the upside is once you’re near the national limit it’s perfectly weighted and full of feedback – albeit, with a slight tendency to tramline. The manual shift feels both substantial and easy to place, it also makes you feel more a part of the drive than the oft-fitted paddleshift of the competition – the exposed mechanism is a work of art too. Then we get to the grip, which is nothing short of a miracle on these damp, cold and leafy early winter roads. But should you wish to work harder, there is a dial under the wheel that allows you to adjust the traction control’s allowed wheel slip – Jenkinson would no doubt have explored that switch far more than we did.

We pull off the A303, taking the back roads towards our first stop at RAF Thruxton. Just over a decade after Jenks’ run, this circuit would see both Jochen Rindt and Graham Hill take to the track in one of the 12’s descendants, the 59B. Both were driving for Roy Winkleman Racing, and both would go on to become Team Lotus F1 legends in the decade that followed. Thruxton is the first of four former airfields on our route, and as a circuit is famous for being one of only a few venues worldwide to never change its layout – our next stop on our list wouldn’t be so lucky.

Heading into Wiltshire for just a moment, we pass Salisbury Cathedral and pick up the A338 towards Ringwood, stopping at what remains of RAF Ibsley. Like Thruxton, Ibsley became an aerodrome and part-time race circuit after the war, but only doubled as a circuit for four years. It hosted only a handful of race meetings, all of which took place on a Saturday due to its close proximity to St Martin’s church in the village, which meant Sundays weren’t permitted. Despite its lack of event history, it remains an important stop for us. On 4 August 1951, Lotus’s first circuit race car, the Mk3, raced on the unusual semi-square circuit – which was not unlike Goodwood in layout – and Chapman took a much needed class win. Both man and car were beginning to get noticed by the motoring press, and a week after Christmas that year the Lotus Engineering Company was formed, a decision that led to the Type 12 Jenkinson piloted all those years ago, and ultimately the Exige we have with us today.

There’s very little left to hint at either the airbase or circuit’s place in history. It was dismantled in the late ’50s for hardcore, before becoming a quarry and eventually a nature reserve. It’s difficult to imagine the roars of P51 Mustangs and Maseratis that would have filled the air over 60 years ago, the only clue being a destitute control tower that looks over the flooded land, where the runways and perimeter roads that formed the circuit used to lay.

With the sun set to drop at any moment, we soon continued on to Ringwood, before turning left onto the A31, and into the New Forest. In search of appropriate backroads, we head towards the site of another former airfield, RAF Stoney Cross. A bomber station in the war, its over-wide A-framed runway layout could have produced a fantastic early motorsport venue. That wasn’t to be, however, due to heavy competition in and around Hampshire and Dorset. As such, Stoney Cross was slowly reclaimed by nature, which means that much of it remains today. Best of all, the main runway is drivable, and we couldn’t resist the opportunity to take the Cup 430 on the sort of terrain where its forefathers triumphed. I try my hardest not to scare the wild horses that take up the ‘grandstands’ on this would-be finishing straight today. As I bounce over this undulating stretch of road with glorious long views in all directions, it’s easy to understand why Hampshire was the county Jenkinson called home for most of his life. There was no shortage of great, wide driving roads to use for his motorsport related mischief.

We return to the A31 for a moment, before taking the back roads towards Farnham via Winchester, Alton and Odiham, where Jenkinson lived for many years in a now unassuming single-storey cottage. Back then his abode was infamous among his writer friends for being without running water, full of clutter and in need of a Fiat 500 engine to generate electricity. One amenity it did apparently have, however, was a personal motorcycle scramble course, which he’d often use in the early hours of the day. It was in the next town of Crondall that Jenkinson allegedly asked the local post lady if she could knit him a jumper with a diagonal black stripe. It was all a ruse in order to fool the authorities in anticipation of seatbelt usage becoming mandatory in 1983.

Not a fan of being told what to do, Jenkinson was particularly disparaging of Dutch rally driver Maurice Gatsonides in print after hearing he was to sell the Gatsometer – a precursor to the speed gun and camera – to police forces across Europe. As we pass the many luminous yellow cameras en route to our final leg, it’s easy to see how Jenkinson could have felt betrayed by someone he thought was ‘one of us’. The evolved technology has led to automatic number plate recognition (ANPR), smart motorways and average speed check zones, all of which would have made his high-octane road tests impossible today.

The Exige Cup 430, despite its lairy silhouette and ferocious supercharged V6 powerplant, is still hugely enjoyable on, and within the rules of, the road. Most of the time it feels like the Elise descendant that it is, and much of the enjoyment the Elise brought with just 118bhp in 1996 remains attainable with nearly 430bhp in 2020. It’s not overly difficult in town either, it’s just the heavy steering, which creeps back into view at around 20 to 30mph and the poor rear visibility that lets the side down a little as we pull into Farnham town centre.

To my eyes, the Cup 430 has long been the most aesthetically pleasing model in the Elise S3’s extended family. Its wide muscular stance fills out the space far better than the ever so spindly Elise, and it has a much more appealing rear wing than the Sport 410, although I’m not overly sure on the Union Jacks to the side. The vivid green on this example, however, is one of my favourite colours and today under Farnham’s Christmas lights it really pops, and manages to hide the 180 miles of road silt we’ve accumulated so far.

The last stop on our trip before turning back to Hartley Whitney is RAE Farnborough – now Farnborough Airport – where the conscientious objector met future friend, collaborator and Motor Sport editor Bill Boddy, who begged him to write professionally after the war. Always a racer first, Jenkinson had a uniquely authentic perspective in racing journalism, and remained a motorsport fan and writer until the very end.

It’s difficult to know what Jenkinson would have thought about our run. Many texts hint to him not being a nostalgic man. For instance in 1995, just one year before his death, he was invited to join Stirling Moss in replicating their landmark Miglia Mille win in their SLR, to celebrate the 40th anniversary. Jenkinson flat out refused, seeing no point in doing a replica event for the fun of it, having done it for real four times in his life. Others paint him in a different light, however, and it’s known he was a prolific hoarder, who was famously unable to get rid of any old car, motorcycle, programme, magazine – a collection of which apparently took up most of his bathtub – and the like.

All we do know is that he was a true eccentric, and it was a great experience trying to get into the mind of this one-off. I hope he would have looked upon our run more favourably than the Miglia Mille ‘jolly’ 25 years ago, as we kept to the spirit of his secretive lap without following it religiously. His anarchic side might have been disappointed that we weren’t left stranded as he was on a stranger’s driveway, awaiting a tow on Christmas day. With that thought, we pulled

back into the Phoenix pub to complete the lap before heading back home, ending our run in the same place as Jenkinson, albeit not in the same low spirits.

When explaining what happened next in his posthumously released autobiography, he had this to say about 25 December 1957: ‘My Christmas dinner? I didn’t have one, but I remember having quite a few beers to drown my sorrows.’

This story first appeared with more images in Absolute Lotus Issue 17. For more like this, subscribe to the bi-montly Absolute Lotus magazine here.